|

Influenza in Miami County and the world

With biographies of Martha Ann Brooks and Anna Otiker

“Spanish

Influenza is rampant in the United States and, according to the statements

given out by the public press, it has now reached practically every state in

the union. Never within the recollection

of people living today has there been an epidemic so widespread or so

disastrous in its results.” The American

Journal Of Nursing, November 1918, Vol XIX, No.2 p.83

Spanish

Influenza was sudden and horrifying. A typical victim would be between the ages

of twenty and forty. They felt fine as

they started their day in the morning.

Heading out to their job, whistling while they approached the

workplace. A sudden high fever would

appear, along with what seemed like cold symptoms. They would feel their sinuses begin to itch

and progress into a stuffy nose and they would begin to feel their body ache.

Then nausea would appear and they would be horrified as they tasted the vomit

erupting from their throats and experienced the incontinence of loose and

foul-smelling stools. Hemorrhaging would

begin from their eyes, ears, nose, and mouth and soon they would develop

pneumonia with their lungs filling up with fluid. They would turn blue and then black as they

struggled for air while their breathing was ineffective because they were

drowning with the fluid filling their lungs.

Death would come and steal them away by dusk. Left behind were wives, or husbands, or

sweethearts. Children were abandoned as

death took away their parents. Funeral

parlors were overwhelmed and bodies piled up.

Cities ran out of caskets. It was

1918 and the deadliest communicable disease of the twentieth century was a

raging killer. The Spanish Influenza did

not target the very young and the very old like most flu. Young adults with the strongest immune systems

had the highest death rate. As a result, it left in its wake a population of

orphans. The disease is believed to have caused an overreaction of the body’s

immune system which caused the lungs to fill with white blood cells and smother

the victim. Twenty-five million Americans got the flu. The Smithsonian

Institute estimates that 670,000 of these people died from it. How did this epidemic affect WWI and what

happened when it reached the sleepy little communities located within Miami

County Indiana?

More

United States soldiers died from the flu than were killed in battle. Influenza

was the leading cause of Army hospitalizations for both officers and enlisted

men. It was the leading cause of death

for US Army troops as over 23,000 Army soldiers’ deaths were the result of the

Spanish Flu. It is ironic that half of the number of deaths of our

Army soldiers during a war was actually from a communicable disease. Hind

sight tells us that the first confirmed case was in Fort Riley, Kansas in March

of 1918, but the American Journal Of Nursing reported at the time that the epidemic

began in New England at a military camp named Camp Devans near Boston and

spread down the Atlantic seaboard. The flu then made its way westward not

stopping till it reached the Pacific coast.

This was actually the second wave of the flu and it took a mere eight

weeks to sweep through the country in September and October of 1918.

While it was prevalent in military training camps, civilians were also

stricken. On October 1, 1918, the United

States surgeon general decided the flu warranted a national response so he

contacted the Red Cross to request it provide nurses and emergency supplies

wherever needed. When the US entered

World War I in April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson assembled a War Council of

business and government leaders to take charge of the American Red Cross.

Wilson's action violated the American Red Cross charter's provisions for

organizational governance but was in keeping with his policy of instituting

temporary government control of railroads and agriculture to mobilize resources

to win the war. The War Council quickly revamped the organization and recruited

eight million female volunteers through the registering of nurses in the

Reserve Home Defense of Nurses. These

reserve home defense nurses were utilized during the high needs of the

influenza pandemic. While The Red Cross response occurred mostly on local

levels and effectiveness varied between locations, they did the following:

- Supplied two million dollars in equipment and medical supplies to

hospitals.

- Established kitchens to feed flu sufferers and houses for

convalescence.

- Transported people, bodies, and supplies.

- Recruited more than 18,000 nurses and volunteers to serve

alongside Public Health Service workers and local health authorities.

- Distributed pamphlets and circulars on how to care for flu victims

and flu prevention.

- Directed its chapters to form influenza committees to work with

local and regional health authorities and Red Cross Divisions.

First demands for nurses came from military camps and then the requests

began to come from civilian hospitals.

As hospitals overflowed the public health nurses and visiting nurses

assumed the main responsibility for providing care. The cities, with their ghettos of immigrants,

became Petri dishes of flu. Nurses

visited tenement houses that were overcrowded and they visited row houses full of

sickness. Away from the cities, the

nurses called on farmhouses, log cabins and mountain shacks which were all

filled with families stricken with flu.

They changed bed linens, bathed patients, and assessed the sick as they

took temperatures, counted pulses and listened to lungs. Nurses fed the ill soups and other liquid

nourishment. Sometimes under the direction

of a doctor, but other times relying on their own experience and knowledge,

they made do with what they had on hand.

Ice packs reduced fever. By

applying mustard plasters and administering cough syrups they attempted to open

airways. They stepped into the role of

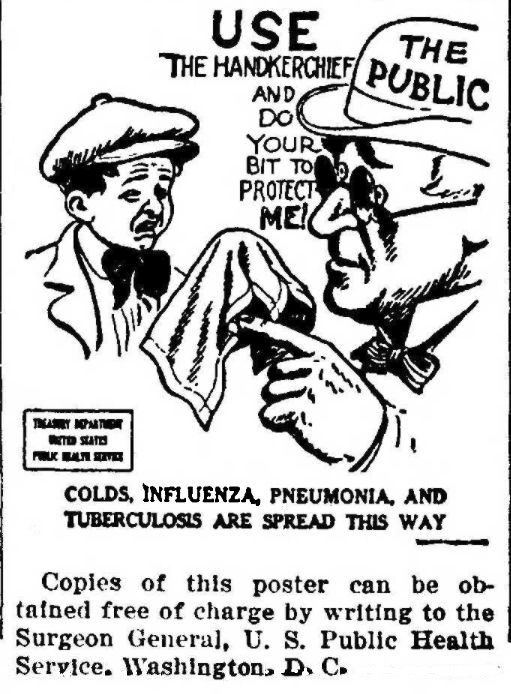

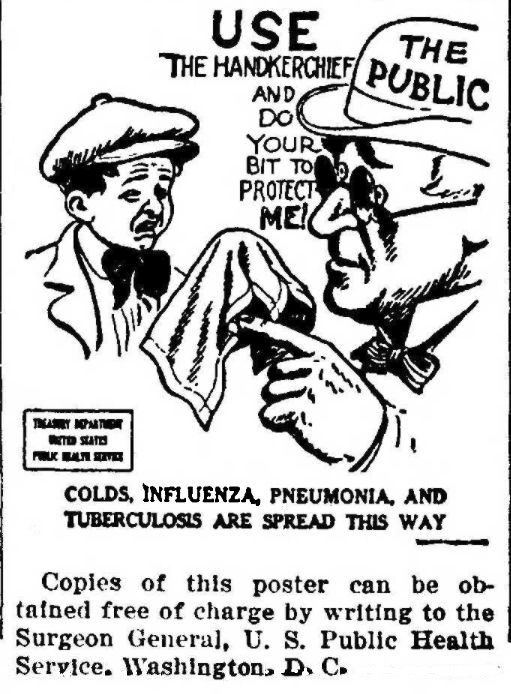

educators as they taught families about basic hygiene, explaining to people the

importance of covering their mouths during coughs and spitting into

handkerchiefs. They told them how they

must boil soiled linens and open their windows to allow fresh air to enter

their homes. And when a family lost a

loved one, it was the nurses that gave comfort to those that were left behind while

washing and preparing the dead body for removal.

“The patient’s

nose and throat discharges should be received only in material that can be

burned, like old muslin, gauze or paper napkins. As soon as they are soiled these handkerchief

substitutes should be placed in strong paper bags and afterward burned,” ~

American Red Cross Textbook on Home Hygiene and Care of the Sick by Jane A

Delano, RN

p117

In

no other epidemic was the mortality of nurses so great and did so many nurses

become ill. Many nurses died from the

flu because of exposure and the fact that the nurses were extremely fatigued

from caring for so many patients. To

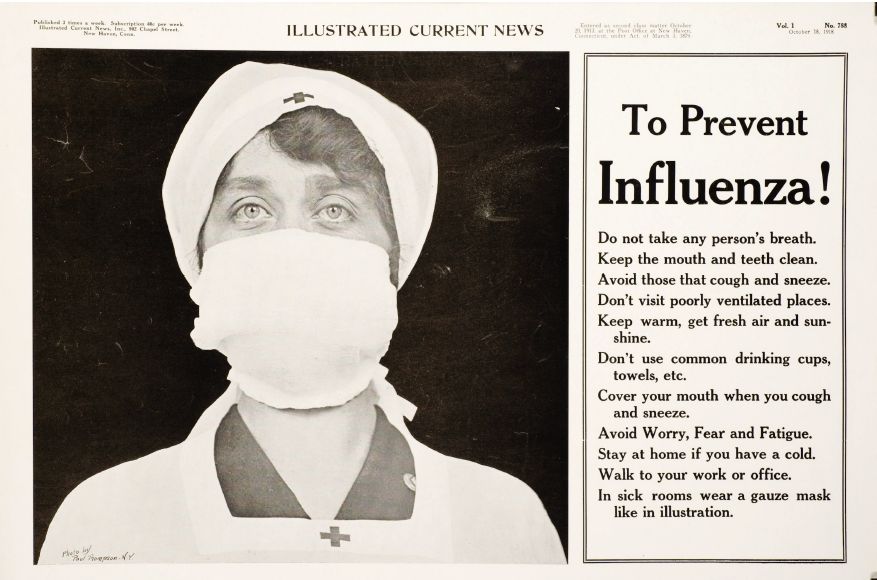

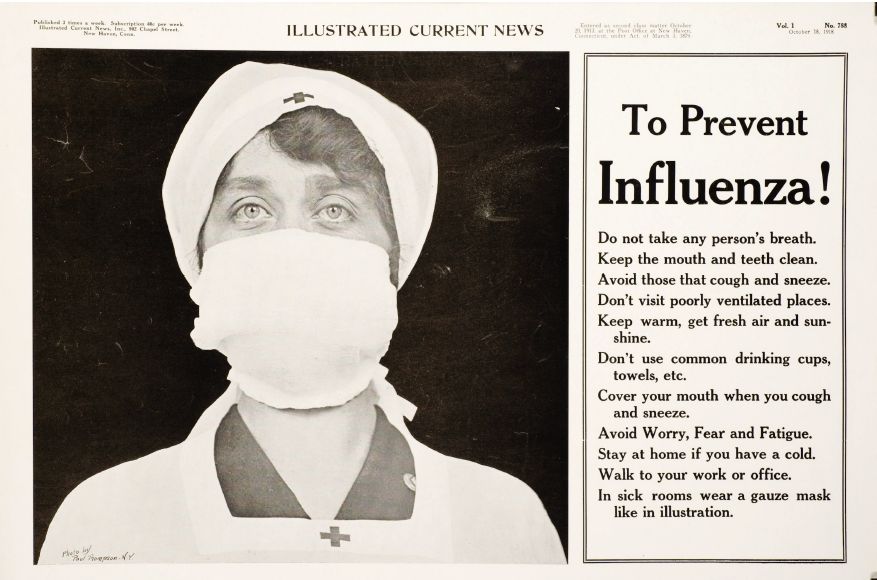

prevent this exposure gauze face masks were created. They were a stitched mask with four

strings. Nurses carried one bag for

fresh masks and one bag for soiled bags. Masks had to be boiled and dried at

the end of each day. Each nurse had

about sixteen masks. As time went on

because so many nurses became sick disposable masks were made of six layers of

folded gauze and the isolation garb was advanced from crepe aprons to long

sleeved “all over” gowns. In the

civilian population, home care nurses wore gowns over their clothes that were

left in the homes of the sick for re-use.

But soon the visiting nurses ran out of them and had to use long sleeved

aprons carried outside the homes wrapped in newspaper. The nurses did not place these aprons in

their nursing bags.

“The Call is for

anyone who has a pair of hands and is willing to help where the need is

greatest,” ~ American Journal Of

Nursing, November 1918.

By

December 1918, the American Red Cross, with such a dire need for nurses, began

to send nurses they had chosen not to select earlier, which included black

nurses and married women, out into the communities and into influenza-ridden

military camps. Most nursing school trained graduate nurses were overseas caring

for soldiers in war-torn areas, which resulted in married women who had stopped

nursing re-entering the field and retired nurses stepping back into their

uniforms. All types of women

volunteered as nurses and aides during WWI.

Most were single but many married women with children also volunteered

as time passed and the need increased.

Most of the women were age 25-35 but some younger women and some older

women stepped forward as well.

As

a result of the nursing shortage during WWI, the position of the nurse aide was

created. Thousands of women had been trained to help using a curriculum titled

“Home Hygiene and Care of the Sick” offered by the Red Cross. It had been created because, since the

knowledge of germs had only been discovered a couple of generations ago, many

people were still ignorant about how to prevent the spread of infection. When the women were taking the Red Cross

course they believed they were obtaining skills to be used in their homes to

care for family members. However, because

so many of the nurses were overseas the need became so great they were called

into war work to assist the nurses in the military hospitals. They were used as nurses’ aides during the

flu epidemic. The course was offered

more frequently and in the twenty months prior to February 28, 1919, over 5,000

classes were held by The Red Cross in “Home Hygiene and Care of the Sick”

during which 80,000 students were enrolled and over 60,000 certified upon the

completion of the courses.

On

the bottom of page five of “The History of the Miami County Chapter American

Red Cross Peru, Indiana” the following is found;

“Nurses Survey: The nurse's

enrollment was taken up by the Council of Defense. In September 1918, this department was turned

over to the Red Cross, but as the work had been practically completed, there

was no record kept simply a cleaning up of the general work which was done by

the vice-chairman. During the influenza

epidemic, two nurses were sent out through the influence of the Miami County

Chapter, namely Miss Martha Ann Brooks and Miss Anna Otiker.”

Who were Martha Ann and Anna, what did they

do, and what became of them?

During the fall of 1918 newspapers were printing statements from The Red

Cross urging nurses to come forward to serve flu-stricken areas. The mining communities of Kentucky and Ohio

were hit even worse than most areas.

Some nurses were needed to travel to hard-hit communities but nurses

were urged to remain in place until sent to another area by the Red Cross. The Red Cross declared caring for flu victims

as war work. Women were also sent to

Army camps. Since the flu was spread by

air droplet when an infected person sneezes or coughs, the close quarters of

the military bases coupled with the worldwide travel taking place during WWI

caused the flu to become prevalent in the army camps. Anna and Martha Ann were likely sent to an

army camp in the Midwest. But in spite

of correspondence with Camp Benjamin Harrison, Camp Sherman, Camp Taylor and

Camp Grant, where they served and what they did has not been discovered. In fact, no nurses by the names of Anna

Otiker or Martha Ann Brooks were discovered in the Miami County records. It is likely that the two women were nurse

aides trained in the “Home Hygiene and Care of the Sick” course and certified

by the Red Cross.

“I saw hundreds

of young stalwart men in uniform coming into the wards of the hospital. Every

bed was full, yet others crowded in. The faces wore a bluish cast; a cough

brought up the blood-stained sputum. In the morning, the dead bodies are

stacked about the morgue like cordwood,” ~Dr. Victor Vaughan acting Surgeon

General of the Army upon visiting Camp Devens near Boston; Early September

1918.

Anna Otiker was born in Ohio in 1862 to a Swedish immigrant father and

an Irish immigrant mother. Her father,

Henry H. Otiker, was a farmer who served in the Civil War. By 1870 the family,

consisting of Anna, her father and mother along with her sister Sophia and brother

Henry ,was living in Miami County on a farm in Richland Township. In 1874 her father was elected to the school

board. In 1880 the family had expanded

to add sisters Elizabeth, Margaret and Zoe along with brothers Alexander and

Ralph. They lived in Paw Paw which, although

prosperous in the late 1840s, would have been a mere ghost town by 1880. After spending time as a substitute mail

carrier and a dry goods store clerk, Anna settled down into the skill set of a

dressmaker by 1920. She grew up as a

childhood friend of Indiana author Ross Lockridge, Sr. They exchanged letters throughout

their lives, and in fact, he sent her a beautiful lavender silk scarf from

Paris. Anna died in 1951 at Logansport

Hospital from complications of arteriosclerotic heart disease. She had been in the hospital three years due

to Cerebral Arteriosclerosis. She was

buried in Paw Paw Cemetery in Peru Indiana.

No

“Miss” Martha Ann Brooks could be discovered in the 1918-time frame in Miami

County, Indiana. There was one Martha

Ann with Brooks as her maiden name who was married long before 1918 and would

have no longer gone by that surname after marriage. There was also a “Mrs.” Brooks whose given

name was Martha Ann. She is a likely

candidate as she is in the same age range as Anna Otiker. There may have been a typo in the Red Cross

report and “Miss” inadvertently typed instead of “Mrs.”. For this reason, Mrs. Frank Ellsworth

Brooks was dubbed by this writer as “candidate one” but the identity of the

Miss Martha Ann Brooks remains unconfirmed.

Nevertheless, Miami County resident, Martha Ann Moeck was born in 1862

in Prussia and came to the United States when she was eleven. By 1880 the Moeck family was living in Peru,

Indiana. Martha Ann’s father’s name was

Albert and her mother’s name was Minnie.

Her three brothers, Gustave, George, and Franklin were living with them. Her father was a wagon maker. In 1909 she married a man 12 years her

junior. He was a widower with three

small sons. Her husband, Frank Ellsworth

Brooks was employed by the railroad.

After her marriage, Martha Ann often used the first letter of her maiden

name as her middle initial. She died in

1943 of cancer and is buried in the Lutheran Cemetery in Peru, Indiana. One problem with her being the person who

served as a nurse during the flu is that of her German origin. She may not have been trusted in the military

camps of the day due to her German heritage.

“Today we serve

best by preventing sickness. Cure of sickness and alleviation of suffering must

never be neglected; not in cure, however, but in prevention lies the hope of

modern sanitary science, of modern medicine and of modern nursing.”

~ American Red

Cross Textbook on Home Hygiene and Care of the Sick by Jane A Delano, RN page

11, 12

In

the Midwest, The Red Cross supplied more than a quarter of a million dollars’

worth of hospital supply items to bases Benjamin Harrison, Sherman and Taylor

to care for soldiers with flu and resulting pneumonia. The capacity for

patients of these three bases was 4,290, however they had 16,167 cases of flu

and pneumonia to care for at one point during the epidemic. The Red Cross sent 11,000 bed sheets, 11,000

towels, 13,100 pillowcases, 8,000 pajamas, 2,500 pill cups, 7,000 wash clothes,

4,500 handkerchiefs, 25,000 paper cups, and 50,000 masks. Also, medicines and medical supplies were

sent as needed. The Red Cross also fed

and housed 400 people daily who were grief-stricken relatives of critically ill

soldiers. Newspaper articles in the fall

of 1918 gave hints for flu care which had been issued by the Indiana State

Board of Health:

“If one feels a sudden chill followed by a headache, backache,

muscular pain, fatigue, and fever GO TO BED AT ONCE. Make sure to have enough bed covers to stay

warm. Open all windows in the bedroom

except during rainy weather. Take

medicine to open bowels freely. Consume

nourishing food every four hours (eggs, egg and milk, or broth) Stay in bed

till the physician says it is safe to get up.

Allow no one else to sleep in the same room. Protect others by sneezing or coughing into a

handkerchief which should be boiled or burned.

Have anyone taking care of you wear a mask.”

Articles went on to explain directions for making

a mask:

“Masks are to be made from four to six folds of gauze and should

cover the nose and mouth and tie behind the head. The masks must be kept clean and put on

outside the sick room. They must be

boiled 30 minutes every time after taking off.”

State officials urged people to avoid crowds in the same way one would

avoid a bad smell. They implored

citizens to cover their mouth with a handkerchief when coughing or sneezing. Spitting was forbidden and all sputum was to

be carefully handled. All public

meetings including church were to be avoided.

In November of 1918 many deaths in Indianapolis were reported with

schools closing their doors and people were mandated to wear masks in public

places.

“I had a little

bird, his name was Enza. I opened the

window and influenza!” ~ children’s playground song circa 1918

On

the twenty-fifth of September in 1918 the local paper announced that the

Spanish Flu had reached Peru, Indiana.

It could not be determined whether travelers brought the flu to Miami

County or the weather should be blamed because the symptoms were much like a

bad cold that kept holding on. Nevertheless, by this date, there were a number

of cases that doctors had diagnosed as Spanish Flu and both doctors and

pharmacists were very busy.

By

October seventh, Peru and Miami County schools, churches, theaters and moving

picture shows were ordered closed. A ban was placed on all public gatherings by the

County Health Department after receiving notice from the State of Indiana who

in turn received their directive from the National level.

Almost every city and town in the country received the same directions. The

tone of the newspaper coverage changed on October eleventh when they issued a

serious warning. Several thousand cases

of flu were reported in Indiana and several hundred deaths had occurred. The

paper explained that infection was spread by oral and nasal secretions and the

person who coughed, sneezed or spit were dangerous. The only meetings or gatherings allowed were

to be Red Cross or Liberty Loan in nature.

Outdoor activities and outside sporting activities were allowed. All

people with colds were to stay at home because the symptoms of colds were

similar to the symptoms of the flu. The

next day the county health officer in Miami County ordered all homes with flu

or suspected flu to be flagged in order to attempt to contain the disease. This

direction also came from the State which ordered Quarantine Placards be placed

on all houses that have people in them with flu. There were ninety cases of flu in Miami

County not including cases in towns. Two

days later it was learned that the Robinson Circus had settled into winter over

with the Wallace Winter Quarters.

Normally they would be doing shows in the warmer southern areas but were

not doing so this year due to the southern states being so hard hit with

influenza. Health authorities had shut

down the gatherings of people for the circus shows. By the end of October five hundred cases of

Influenza were reported in Miami County with one hundred being in Peru. This was much milder than many communities

were experiencing. People were

admonished that this was due to county health regulations and precautions,

therefore it was important to continue to follow these rules. Four people had died in Peru and an

additional fourteen deaths had occurred from flu throughout the county. A number of additional deaths had occurred

from pneumonia which developed after the flu.

Four of the deaths from secondary pneumonia were circus employees. County Farm deaths were not reported to

county health officials. People were

again reminded not to congregate in pool halls or cigar rooms. Schools, movie

picture shows, theaters, churches were all banned. On the last day of October, the paper

reported that while the quarantine was not yet raised it was expected to be

over soon.

On

the ninth of November, Denver and Mexico schools in Jefferson township

re-opened after being closed for four weeks due to flu. But by the twentieth, it was noted that after

lifting the bans for two weeks 175 more cases of flu were reported in Peru. And by the twenty-third, the influenza

epidemic was reported to be increasing in Peru and Miami County. People were urged again to avoid crowds and

postpone meetings as thirty-six new cases of flu had been reported in twenty-four

hours. Two hundred cases had erupted in

November with a total of six deaths in the city of Peru since the first of

November. People were encouraged to

stay out of dimly lit, poorly ventilated public places and to let plenty of

fresh air into the living and sleeping rooms in their homes at all times. In fact, the city of Peru was placed under

quarantine by order of the Board of Health.

It was reported on the twenty-seventh that eight members of one family

had the flu. This unfortunate family had

nine family members and their 17-year-old son was hospitalized. Only the mother had remained healthy. On the

last day of November, Amboy reported worsening flu. Schools had not been banned but many students

were absent due to either being ill or afraid to attend due to the epidemic. Several new cases of flu were being reported

on a daily basis. Mexico public school and orphans school were closed as were

Chili, Gilead, Akron and Roann Schools.

They were expected to remain closed for one week.

In

the middle of December, it was reported that the November death rate of flu or

secondary pneumonia as a result of the flu was fifteen for November 1918. This did not include deaths at Wabash

Railroad Employees Hospital. The situation in Peru was not

as serious as earlier in the fall but people were urged to continue to take

precautions throughout the entire winter.

The disease was not expected to run its course until spring. People were reassured by the third week

December that Miami County was not as hard hit as the surrounding counties but

cautioned that new cases continued to develop daily and precautions were to be

maintained by all. By the end of the

month, the paper was reporting that only two new cases of flu had appeared that

week and both were in homes that already had cases of the disease. No new homes

were stricken with the disease.

“It cannot be too

strongly emphasized that the chief agent in the spread of human disease is man

himself. And the human hand is the great

carrier of disease germs both to and from the body.” ~ American Red Cross Textbook on Home

Hygiene and Care of the Sick by Jane A Delano, RN page 19

The

Spanish Influenza of 1918 had a major impact on the outcome of WWI. Not only did many soldiers die from the

disease, but President Wilson is believed to have been ill with the flu when

the Treaty of Versailles was negotiated and therefore less able to negotiate

what he believed to be a fair treaty for all parties. The flu also left many orphans to grow up

without intact family units, and left no choice except for many young women to

remain single throughout their lives due to the lack of young men left alive in

their age group. But an even more

significant result of the flu epidemic that fateful fall was the revelation

that most people did not understand personal and family hygiene. This resulted in an increase in education of

the general public on how germs are spread.

In the long run, Americans improved their overall health and lengthened

their lives as a result of this horrible disease. The medical community rallied to gain a

better understanding of how the flu works.

They also learned more about immunity, bacteria, and viruses because of

this epidemic. Therefore, out of this

tragic loss of life grew progress from which society continues to benefit.

|

Works Cited

“1918 Flu Pandemic.” Wikipedia,

Wikimedia Foundation, 18 Feb. 2018.

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic.

“The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918:

baldheretic. “The Flu Pandemic Song.”

YouTube, YouTube, 8 Feb. 2008.

Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: the Epic Story

of the DeadliestPlague in History. Penguin, 2010.

“ ‘BillionGraves Index," Ann Otiker, Died 16 Jan 1951,

Burial at Paw Paw Cemetery,

Richland, Miami, Indiana, USA.”

“City Must Again Be Under The Ban and Quarantine.”

The Sentinel, 23 Nov. 1918.

Indiana State Board of Health. Anna Otiker Death Certificate

Delano, Jane A., et al. American Red Cross Text-Book

Delano, Jane A. “The Red Cross.” The American Journal

Of Nursing,Dec. 1918, pp. 185–188.

JSTOR [JSTOR]. Vol 19 Issue 3

“Eight In Family Down.” The Sentinel, 27 Nov. 1918.

“The Epidemic of Influenza.” The American Journal Of Nursing,

Nov. 1918, pp. 83–90. JSTOR. Volume 19 Issue 2

Erkoreka, Anton. “Origins of the Spanish Influenza Pandemic

“Find A Grave Index," Anna Bell Otiker, 1951; Burial,

Miami, Indiana, USA, Paw Paw Cemetery

“Five Hundred Cases Of Influenza.”

The Sentinel, 30 Oct. 1918.

“Flu Killed More World War I Troops than Any Battle.”

- World War I Centennial,The United States

World War One Centennial Commission.

“Flu Situation Improving.” The Sentinel, 28 Dec. 1918.

Foley, Edna A. “Department of Public Health Nursing.”

The American Journal of Nursing, Dec. 1918,

pp. 189–195. JSTOR [JSTOR]. Vol 19 Issue 3

Hall, Diane Gould. “100 YEAR ANNIVERSARY OF THE

“Health Notice.” Sentinel, 23 Nov. 1918.

History of the Miami County Chapter of the American

History.com Staff. “Spanish Flu.” History.com, A&E

Television Networks, 2010.

"Influenza Precautions, Then and Now," U.S. National

Library of Medicine

“In Flew Enza.” YouTube, Various Artists, 24 May 2015.

“ ‘Indiana Marriages, 1811-2007," Frank E Brooks and

“Influenza 1918.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service.

“Influenza Epidemic.” The Sentinel, 30 Nov. 1918.

“The Influenza.” The Sentinel, 23 Oct. 1918.

“Influenza Situation Causing Much Concern.”

Sentinel, 23 Nov. 1918.

“Influenza Situation.” The Sentinel, 14 Dec. 1918.

“Influenza To Be Quarantined at Once.”

The Sentinel, 12 Oct. 1918.

“John Robinson Circus Here For Winter.”

The Peru Journal, 14 Oct. 1918.

“Letter to Anna Otiker from Earl Lockridge, Sr.”

Miami County Museum, 15 Sept. 1927,

Peru, Indiana, Indiana.

“Letter To Anna Otiker from Earl Lockridge, Sr.”

Miami County Museum, 30 Sept. 1927, Peru, Indiana.

Loman, Cindy. “Harry Thetford: Flu Killed More World War I

Martha Ann Moeck Brooks Death Certificate.

Indiana State Board Of Health.

“Meet To Discuss Influenza Situation.”

Sentinel, 21 Dec. 1918.

Mullen, Thomas. The Last Town on Earth.

Random House, 2007.

“New Orders Issued By The Health Board.”

Unknown Newspaper, 12 Oct. 1918.

Noyes, Clara D. “The Red Cross.” The American Journal

Of Nursing, Nov. 1918, pp. 108–112. JSTOR [JSTOR].

Vol 19 Issue 2

Noyes, Clara D. “The Red Cross.” The American Journal

Of Nursing, Oct. 1918, pp. 25–31. JSTOR [JSTOR].

Vol 19 Issue 1

“Number Schools Closed.” The Sentinel, 30 Nov. 1918.

“Nurses Wanted.” The Sentinel, 30 Oct. 1918.

“People Should Avoid Mingling in Crowds.”

The Sentinel, 20 Nov. 1918.

“Peru City Directory.” Peru City Directory, 1919, p. 126.

“Quarantine Not Raised.” The Peru Journal, 31 Oct. 1918.

R, G. “Experiences During the Influenza Epidemic.”

American Journal Of Nursing, Dec. 1918,

pp. 203–205. Vol 19 Issue 3

Rosenberg, Jennifer. “1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic

Scarf. Peru, Indiana. Scarf sent to Anna Otiker from

Earl Lockridge,Sr. from France during WWI.

Held by Miami County Museum, Peru Indiana.

Society, National Geographic. “Influenza Photos,

“Spanish Influenza Has Reached Peru.”

Sentinel, 25 Sept. 1918.

“Spread Of Influenza Causes State Health Officers To

Tice, Ida M. “Christmas and The Nation At Peace.”

The American Journal of Nursing, Dec. 1918,

pp. 153–158. JSTOR [JSTOR]. Volume 19 Issue 3

“‘United States Census, 1870," Database with Images,

FamilySearch (Https://Familysearch.org/Pal:/

MM9.1.1/MX63-N13 : 12 April 2016), Anna Oliker

in Household of Henry Oliker, Indiana, United States;

Citing p. 9, Family 67, NARA Microfilm Publication

M593 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and

Records Administration, N.d.); FHL Microfilm 545,842.”

“ ‘United States Census, 1880," Database with Images,

FamilySearch (Https://Familysearch.org/Pal:/

MM9.1.1/MH9T-R9K : 14 August 2017), Martha

Moeck in Household of Albert Moeck, Peru,

Miami, Indiana, United States; Citing Enumeration

District ED 120, Sheet 549A, NARA Microfilm

Publication T9 (Washington D.C.: National Archives

and Records Administration, N.d.), Roll 0298;

FHL Microfilm 1,254,298.”

“ ‘United States Census, 1880," Database with Images,

FamilySearch(Https://Familysearch.org/Pal:/

MM9.1.1/MH9T-XCJ : 14 August 2017), Anna B

Otiker in Household of Henry Otiker, Richland, Miami,

Indiana, United States; Citing Enumeration District

ED 114, Sheet 441D, NARA Microfilm Publication T9

(Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records

Administration, N.d.), Roll 0298; FHL Microfilm 1,254,298.”

“ ‘United States Census, 1900," Database with Images,

FamilySearch(Https://Familysearch.org/Pal:/

MM9.1.1/M9MX-PTN : Accessed 21 February 2018),

Martha M Moeck in Household of Elbert Moeck,

Peru Township Peru City Ward 4, Miami, Indiana,

United States; Citing Enumeration District (ED) 106,

Sheet 13A, Family 293, NARA Microfilm Publication

T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and

Records Administration, 1972.); FHL Microfilm 1,240,393.”

“‘United States Census, 1910," Database with Images,

FamilySearch

(Https://Familysearch.org/Pal:/MM9.1.1/MK53-PQK :

Accessed 20 February2018), Anna Otiker in Household

of Earl Wilson, Peru, Miami, Indiana, UnitedStates;

Citing Enumeration District (ED) ED 123, Sheet 6A,

Family 87, NARAMicrofilm Publication T624 (Washington

D.C.: National Archives and RecordsAdministration, 1982),

Roll 371; FHL Microfilm 1,374,384.”

“ ‘United States Germans to America Index, 1850-1897,"

Database, FamilySearch(Https://Familysearch.org/Pal:/

MM9.1.1/KDS7-ZLP : 27 December 2014), Martha

Moeck, 11 Jul 1873; Citing Germans to America

Passenger Data File, 1850-1897, Ship Leipzig, Departed

from Bremen, Arrived in Baltimore, Baltimore, Maryland,

United States, NAID Identifier 1746067, National Archives

at College Park, Maryland.”

“ ‘United States Germans to America Index, 1850-1897,"

Database, FamilySearch(Https://Familysearch.org/Pal:/

MM9.1.1/KDS7-ZLT : 27 December 2014), Martha Moeck,

11 Jul 1873; Citing Germans to America Passenger Data

File, 1850-1897, Ship Leipzig, Departed from Bremen,

Arrived in Baltimore, Baltimore, Maryland, United States,

NAID Identifier 1746067, National Archives at College

Park, Maryland.”

“Warnings Given Peruvians to Check Disease.”

Unknown Newspaper, 12 Oct. 1918.

Wills, Matthew. “THE FLU PANDEMIC OF 1918, AS

Article written and submitted by: Mary Rohrer Dexter

|